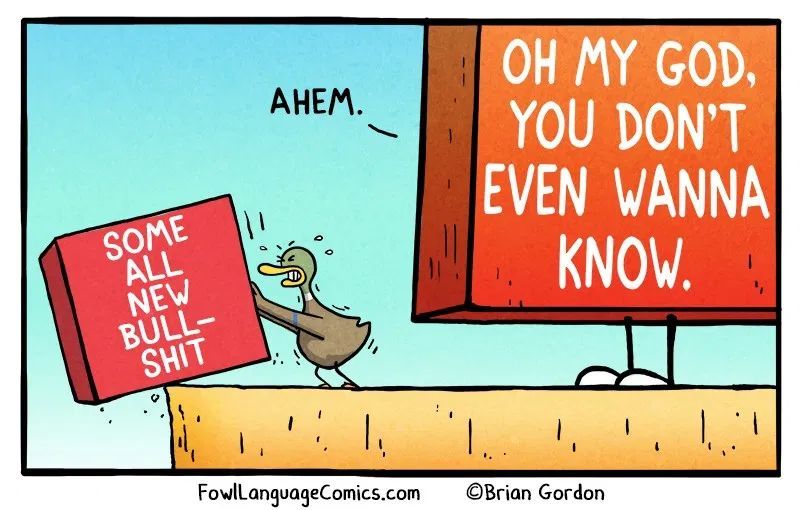

President Trump's idiotic tariff trade war could start tanking the economy soon. I mean, there is already damage being done as chaotic changes drive down business confidence. There's a real dynamic of "expectations drive reality" as mixed expectations for the future, lead to companies throttling back investments now, which leads to economic contraction and job loss (i.e, recession or even depression) in the near future. But there's more to it than just expectations driving reality. There's also reality driving reality.

In the past week I've written about the impact of Trump's new tariffs vis-a-vis price increases and shortages in the US. Friends and acquaintances are doing everything from stockpiling food to moving up purchases of major electronics. But there's more than just the impact to us as buyers.

I mentioned the fact that container deliveries are down 25%+ year over year at major US ports. Markedly less trade at ports means less work for port workers. That job loss will extend downstream to trucking and rail work, too. Oh, and if/when it gets to the point that shelves in stores are bare, stores will lay off workers. And as port workers, truckers, railroad operators, and everyone involved in the retail supply chains start to lose jobs, everything in the economy that serves workers with jobs— restaurants, stores, car dealers, the travel and leisure industry, etc.— will see reductions, too.

But wait, there's more.

Exports are suffering under reciprocal tariffs. You thought China was going to knuckle under just because we slapped a 125% tariff on them? No! Even an idiot— except a big orange one and his sycophants— could have predicted they'd say, "Ha ha, fuck you, here's a 125% tariff for you!" And that's exactly what they did.

The thing about a 125% tariff is it's essentially a killer. It kills trade, it kills exports on affected products, because there are few cases where consumers are going to pay that much more.

I heard a story in that vein on the radio a few days ago. Journalists were interviewing a man who owns a pig farm. He ships most of his pork to China, and the Chinese are canceling their orders now. He wasn't optimistic about being able to find buyers in other countries to replace all that business.

I did a bit of research since hearing that story on the radio. Pork production in the US is a 28+ billion dollar a year industry. Over 30% of it exports. (Source: National Pork Board 2024 statistics.) China is the second largest export market. Exports to China may drop essentially to zero as prices to Chinese consumers increase to unsustainable levels. Exports to other countries may drop off substantially, too, as they contend with lesser tariffs (less than 125%, anyway) that still drive major drops in demand.

So there you have it. The impending tariff disaster is not just, "Oh, no, I can't buy a cheap TV anymore!" but job losses across all industries, including and down to manufacturing and agriculture.

In the past week I've written about the impact of Trump's new tariffs vis-a-vis price increases and shortages in the US. Friends and acquaintances are doing everything from stockpiling food to moving up purchases of major electronics. But there's more than just the impact to us as buyers.

I mentioned the fact that container deliveries are down 25%+ year over year at major US ports. Markedly less trade at ports means less work for port workers. That job loss will extend downstream to trucking and rail work, too. Oh, and if/when it gets to the point that shelves in stores are bare, stores will lay off workers. And as port workers, truckers, railroad operators, and everyone involved in the retail supply chains start to lose jobs, everything in the economy that serves workers with jobs— restaurants, stores, car dealers, the travel and leisure industry, etc.— will see reductions, too.

But wait, there's more.

Exports are suffering under reciprocal tariffs. You thought China was going to knuckle under just because we slapped a 125% tariff on them? No! Even an idiot— except a big orange one and his sycophants— could have predicted they'd say, "Ha ha, fuck you, here's a 125% tariff for you!" And that's exactly what they did.

The thing about a 125% tariff is it's essentially a killer. It kills trade, it kills exports on affected products, because there are few cases where consumers are going to pay that much more.

I heard a story in that vein on the radio a few days ago. Journalists were interviewing a man who owns a pig farm. He ships most of his pork to China, and the Chinese are canceling their orders now. He wasn't optimistic about being able to find buyers in other countries to replace all that business.

I did a bit of research since hearing that story on the radio. Pork production in the US is a 28+ billion dollar a year industry. Over 30% of it exports. (Source: National Pork Board 2024 statistics.) China is the second largest export market. Exports to China may drop essentially to zero as prices to Chinese consumers increase to unsustainable levels. Exports to other countries may drop off substantially, too, as they contend with lesser tariffs (less than 125%, anyway) that still drive major drops in demand.

So there you have it. The impending tariff disaster is not just, "Oh, no, I can't buy a cheap TV anymore!" but job losses across all industries, including and down to manufacturing and agriculture.

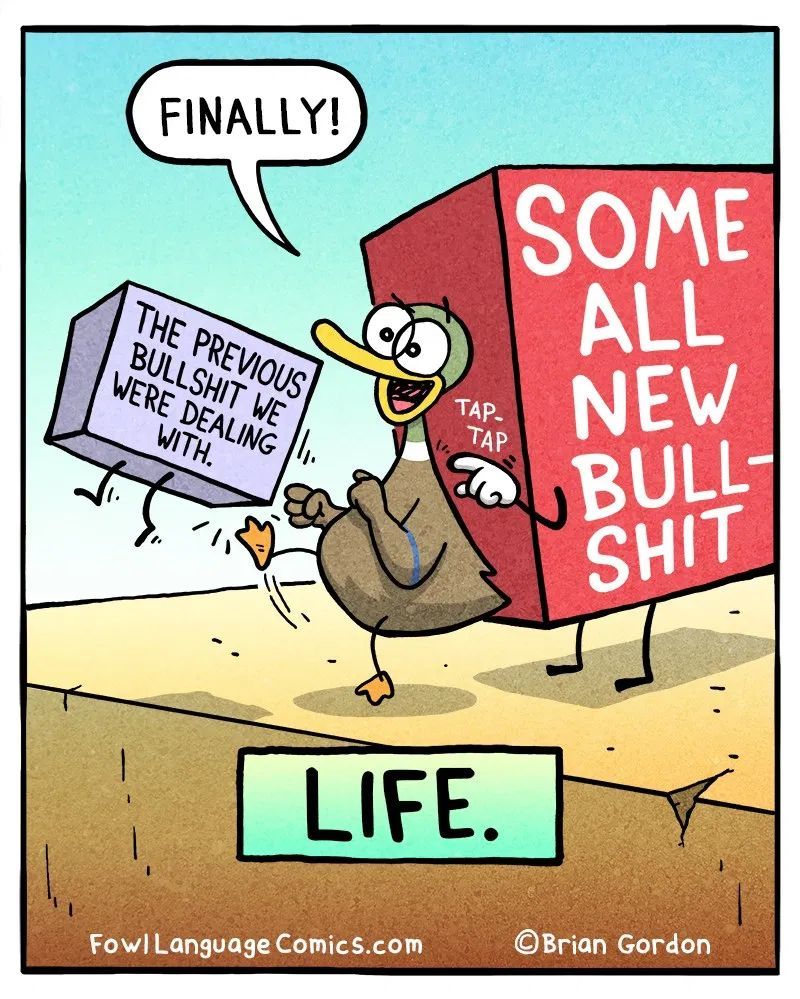

In the past I'd wondered if something could happen that's so overwhelming it's headline news in every category simultaneously— politics, money, health, life, entertainment, sports, etc. In 2020 exactly that happened.

In the past I'd wondered if something could happen that's so overwhelming it's headline news in every category simultaneously— politics, money, health, life, entertainment, sports, etc. In 2020 exactly that happened.

As we close the book on 2020— or slam it shut— it's tempting to think how much better 2021 will be. And probably it will be better. Coronavirus vaccines were developed in record time (not actually surprising in light of the science behind the development but still historically fast) and are now available. As they roll out across 2021 we may not vanquish Coronavirus but should at least beat it down that life can largely resume pre-2020 normality.

As we close the book on 2020— or slam it shut— it's tempting to think how much better 2021 will be. And probably it will be better. Coronavirus vaccines were developed in record time (not actually surprising in light of the science behind the development but still historically fast) and are now available. As they roll out across 2021 we may not vanquish Coronavirus but should at least beat it down that life can largely resume pre-2020 normality.